The production of cheese encompasses many fundamental chemical engineering processes. The raw milk is first pasteurized, then the milk fat content is adjusted through standardization using membrane filtration, after which the milk is placed in a vat. To begin fermentation, microorganisms are added to the milk, followed by rennet to cause coagulation. Once the cheese has had sufficient time to settle, mechanical knives run through the vat slicing the cheese, and the vat is stirred to cook the cheese. Following this, the whey is drained, and the curds are sent to be milled, salted, and eventually pressed. After quality control, the cheese is packaged and prepared for shipping.

Preparation

The first step in the production of milk is the pasteurization and standardization of the raw milk.

Pasteurization

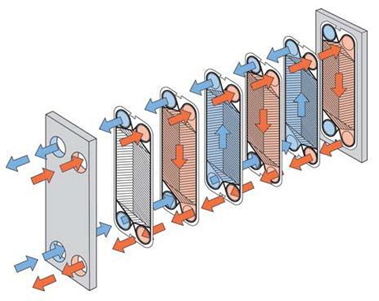

Pasteurization is a critical step to kill microbes and ensure safe mass production. Industrial pasteurizers contain three compartments: Preheat, final-heat, and cooling. Normally a plate and frame heat exchanger, pictured below, is used at medium pressures to heat the milk up to a proper temperature, and water is used as the heating medium.

High-temperature short time (HTST) pasteurization is the most typical form of pasteurization. Most industrial-size HTST pasteurizers have a target temperature of 70 °C with a hold time of 20 seconds, where the hold time is how long the milk is kept at the specified temperature. Alternatively, ultra-heat treating (UHT) brings the milk up to 135 °C for a hold time of two seconds. For safety purposes, it is favorable to heat the milk for longer, but that can leave it tasting burnt. Leaving the milk at elevated temperatures for long periods of time could also denature the proteins, which could upset the curd bonding process later. Pasteurization planning focuses on optimizing for all these considerations. Spray cooling must be used to quickly cool the milk after pasteurization.

Standardization

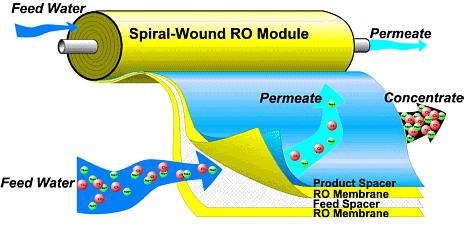

Standardization allows for product differentiation into, for example, reduced-fat and full-fat products. Standardization can happen in a variety of membrane filtration units, including hollow fiber, tubular, flat sheet, and spiral-wound filters. Microfiltration, ultrafiltration, and nanofiltration are used, with varying degrees of filtration accuracy. Standardization helps achieve a specific fat content level of the cheese, and there are also specific pH and protein level requirements for each type of cheese.

Production

Cheese Coagulation

Once the milk has been treated it is placed in a vat. Unlike yogurt, cheese goes through an aerobic fermentation. Here, fermenting microorganisms are added to inoculate the cheese. This is the process through which bacteria create lactic acid from lactose. This acidification of the cheese in turn assists coagulation, helps prevent spoilage and pathogenic bacteria from growing, and contributes to cheese flavor and texture. Following this process, cheese is produced by coagulating the milk using rennet, a complex set of enzymes that interact with the milk proteins to separate them into liquid whey and solid curds.

In this step the cheese is being made as it is stirred appropriately and heated. The curd size, pH, bacteria choice, mold choice, aging conditions, and this agitation are critical in this step of cheese production. The more the cheese is agitated, the more liquid it expels.

Cheeses are cooked in a variety of ways. Processed cheeses, such as cheddar cheese, have low moisture and lower required extrusion temperature relative to other cheeses, making them ideal candidates to be cooked by extrusion. A twin-screw extruder is pictured below. Many other types of cheese are cooked within the vat.

Sizing and Quality Modifications

Once the milk has been converted to curds and whey, the undesired whey is drained off and used to make whey cheeses and whey protein. The cheese curds are then milled. Much of the size reduction is performed in the vat by mechanical knives; however, rollers with teeth are also used to grind the cheese further. If necessary, the cheese is salted on a conveyor by either dry or brine salting to preserve the cheese naturally. The salt allows more whey to be removed from the curd and be drained off. Cheeses such as cottage cheese and cream cheese do not need any further processing and are ready to be packaged and shipped at this point.

Other cheeses are put into a mold of the desired final shape. Then, if required, the cheese is pressed in either a horizontal or vertical cheese press. Vertical cheese presses, such as the one pictured below, have more flexibility in both the types of cheeses they can process and the pressure they can provide. The amount of pressing determines the moisture content of the cheese.

All cheeses except fresh cheeses are ripened to help them acquire a characteristic taste. Certain cheeses take up to 30 years to ripen, but the goal of the industry is to maximize the efficiency of this process without sacrificing quality. Aerators, fans, and other equipment can be used to speed up the process.

Quality Control and Packaging

Quality Control

Any food product must undergo quality control to ensure that the delivered product is up to the proper product and food safety specifications. For cheeses this includes that it meets the proper fat, pH, and protein levels. The food industry is subject to some of the most rigorous contamination and quality standards of any industry, making quality control critical. Some critical quality measures in the cheese process are ensuring correct pasteurization temperature is reached, pH tests at all stages, testing curds before molding, testing firmness after brining, and sterilization of equipment.

Packaging and Shipping

Most industrially-served cheese is packaged in plastic film. Vacuum packs, shrink wraps, and cellophane wraps are used, which provide the advantage of letting the consumer see the cheese. For soft cheeses, a semi-permeable paper wrap is often used, with a stiffer cardboard or metal exterior.

Acknowledgements

- Alfa Laval, Richmond, VA

- Baker Perkins Group Ltd., Grand Rapids, MI

- Excel Water Technologies Inc., Ft. Lauderdale, FL

- Savage Engineering, Inc., Garfield Heights, OH

- Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, Inc., Madison, Wisconsin

References

- Barrys Bay Cheese, 11 Feb. 2008. Web.

- Caldwell, Gianaclis. Mastering Artisan Cheesemaking: The Ultimate Guide for Home-scale and Market Producers. Chelsea Green, 2013. Print.

- Caldwell, Gianaclis. The Small Scale Cheese Business: The Complete Guide to Running a Successful Farmstead Creamery. Chelsea Green, 2014. Print.

- “CDR Cheese Plant Equipment.” Center for Dairy Research. University of Wisconsin – Madison. Web. 22 Mar. 2017.

- “Cheese Production.” Cheese Production | MilkFacts.info. Milk Facts, n.d. Web. 11 Apr. 2017.

- Dustin Meldrum, personal communication, 2017.

- Kindstedt, Paul. American Farmstead Cheese: The Complete Guide to Making and Selling Artisan Cheeses. N.p.: Chelsea Green Pub., 2005. Print.

- “Microfiltration: Spiral-Wound Elements.” Synder Filtration. Snyder Filtration. Web. 1 Apr. 2017.

- “Pasteurization.” International Dairy Foods Association. N.p., 12 Feb. 2016. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

- Scott, R., R. K. Robinson, and R. A. Wilbey. Cheesemaking Practice, 1998. Print.

- Tamine, A.Y. Processed Cheese and Analogues. N.p., Jul. 2011. Print.

Developers

- Fritz Hyde