Freezing food provides a measure of preservation by hindering the growth of bacteria, slowing down enzymatic degradation, and inhibiting oxidation. Frozen foods include several types of processed foods which are frozen for long-term preservation before consumption. The general frozen food process includes unit operations to prepare ingredients, produce and preserve the food by freezing, and finally package the frozen food. The following sections describe these operations and relevant industrial equipment used in each operation.

Ingredient preparation

The preparation stage covers a broad range of operations depending on the type of food being processed, as described below.

Fruits and Vegetables

Fruits and vegetables are harvested and sent to food processing plants, where they are individually prepared through washing, grading, cutting, blanching, and peeling. In general, fruits are cut, trimmed, and/or cored before blanching, while vegetables are typically blanched prior to these steps to soften them and loosen their skins.

Washing and Grading

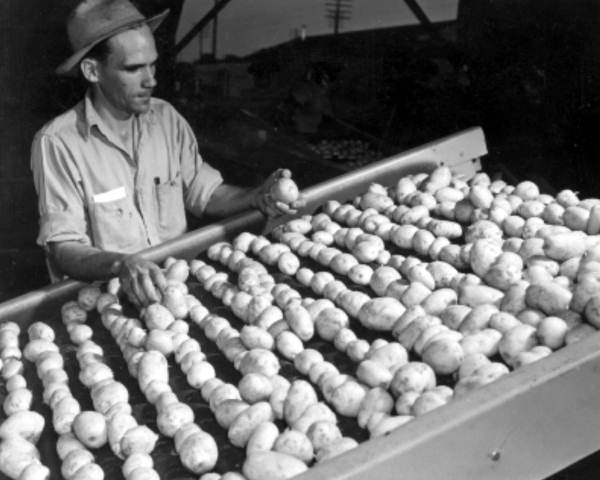

After being harvested, whether mechanically or by hand, produce is washed and sorted. In washing, the fruit or vegetables move along a conveyor belt or agitating/revolving screens while being washed with high-pressure streams of water to remove external contaminants such as dirt. In the continuous process, the produce is next passed onto screeners or rollers that sort for size, with significantly undersized specimens and particulate contaminants falling through as waste. The desired produce is then further sorted, or “graded” according to maturity, size, and shape. Grading may be performed manually as shown below, although newer optical sorting methods, using pulsed LED light to quickly sort food according to configurable quality and size thresholds, are faster and more accurate.

Cutting, Trimming, and Coring

After grading, both fruits and vegetables are further processed through cutting, trimming, and coring. These steps ensure that a ready-to-eat, high-quality product is delivered, without the need for further preparation by the consumer. Produce may be cut, sliced, and cored through the use of mechanical appliances similar to the mechanical peeler shown in the Peeling section below. The individual pieces are held or skewered in place while a blade performs the required operation, and the produce moves along a conveyor to the next step in processing.

Stiffer vegetables, such as carrots, potatoes, or cabbage, may also be finely cut or shredded in a mechanical cutting machine. In industrial use, the washed and graded produce is conveyed into the top of the machine, which it passes through for shredding, before falling onto another belt where it is transported to further processing.

Blanching

The blanching, or cooking, of fruits and vegetables primarily serves to preserve their nutrients and sterilize any lingering microorganisms, extending the shelf-life and quality of the final product. The cut fruits or vegetables are immersed in temperature-controlled boiling water or steam to inactivate their enzymes and neutralize any remaining microbial presence, and then rapidly cooled to prevent further cooking. Blanching ensures lasting quality but must be timed precisely according to produce type and size, as under or over-blanching actually stimulates enzymatic activity and leads to a loss of flavor, color, vitamins, and minerals. This step also facilitates later processing, softening produce, and loosening peels.

As stated previously, vegetables are generally blanched before other preliminary cutting, trimming, or coring steps, while for fruits the order is reversed. Vegetables also typically require longer, higher temperatures as a result of their low acidity relative to fruits and need longer blanching times to neutralize microorganisms and develop a palatable final texture and flavor.

Peeling

Peeling removes the skin of the produce. Depending on the type of fruit or vegetable, as well as company preference, this may be accomplished through mechanical peeling, steam peeling, or lye peeling.

Mechanical peeling, such as using a blade to peel a rotating orange, is typically used for fruits. Other types of equipment, such as abrasion devices and rotating sieve drums, are also common.

Steam peeling, especially used with vegetables, takes advantage of high-temperature steam under high pressure to loosen the skins of produce. Fruits or vegetables are placed in an insulated retort, which may rotate or otherwise agitate its contents to facilitate peel removal. When the pressure inside the retort is suddenly released, steam under the skins rapidly expands and pops the skins. After steaming, the retort contents are fed through a hopper below the retort onto a roller coated conveyor or pinch roller, where the skins are pulled away under a spray of water.

Lye peeling, the preferred peeling method for coarse root vegetables, is accomplished by conveying or submerging produce through a hot solution of lye (sodium hydroxide). The alkali solution is extremely caustic and requires a post-wash in a revolving drum fitted with water sprays to remove residual lye. To sufficiently render the product safe for consumption and wash away the loosened peels, the water sprays reach pressures of 80 – 100 psi. Once thoroughly rinsed, the final taste of the produce should be unaffected.

Meats and Seafood

Similar to the ingredient preparation steps for fruits and vegetables, meat and seafood products are cleaned, and portioned. The methods of washing and grading are extremely similar to the above process for fruits and vegetables.

Cutting and Trimming

After being collected from slaughter conditions meats undergo size reduction by cutting for ease in handling and heat dissipation during freezing as seen below. Seafood is sent to processing facilities for gutting, filleting, descaling, and washing. These processes are usually performed manually by factory workers.

Once the food has gone through these stages, some food items may be packaged prior to freezing such as certain meat cuts, poultry, finfish products, and prepared foods.

Production

After preparation, the ingredients are frozen to preserve the final frozen food product. The freezing process must be performed quickly to hinder ice crystallization, which can have negative effects on the final product. The following sections describe the freezing operation for meats, seafood, fruits and vegetables, and prepared foods.

Meats

The operation used to freeze meat portions depends on their size upon leaving the preparation unit. In general, for meats ranging from a whole carcass to reduced meat trimmings, air-blast freezers are used in a tunnel or a cold storage room configuration. For finer and thinner cuts such as slices of deli meats, the items are usually pre-packed in a plastic wrap and plate freezers are used to individually quick – freeze them. If meats are frozen at a slower rate, the water will have time to form ice crystals, which can destroy proteins, break cells, and cause water loss, leading to a sub-par product, so quick freezing is particularly important when processing meats.

Seafood

Upon arrival at the freezing facility, seafood, ranging from shellfish to finfish and precooked fish, can be frozen using an air blast freezer in a spiral or tunnel configuration. For fish fillets and secondary finfish products that have already been wrapped in plastic liners, plate freezers, are used due to the prepacked nature as well as the shape of this product.

Fruits and Vegetables

After having been sorted and blanched in the preparation stage, fruits and vegetables, ranging from leafy greens to particulate sizes, are put into an air-blast freezer. Small items are best frozen using air-blast freezers because they provide good surface contact between the freezing medium and the product. For small items such as diced mushrooms, carrots, and peas, a tray tunnel design would be the most efficient configuration because it allows the product to be continuously met with a high-velocity air stream as it is fed into the tunnel. A fluidized bed freezer can also be used to freeze delicate fruits and vegetables such as cherries, strawberries, and broccoli florets because it possesses a fluidizing zone that can individually freeze products quickly.

Prepared Foods

Products such as microwavable dinner trays, stuffed pasta, and pre-baked goods are best frozen by cryogenic freezing due to its ability to quick-freeze the crusts of these food items. For pre-packaged marinated products, ranging from poultry to seafood, a nitrogen liquid immersion freezer is most suited since they can safely be bathed in liquid nitrogen. This method of freezing is typically paired with a spiral air blast or cryogenic freezer.

Packaging

Food products that were not packaged prior to freezing are packaged using either non-preservative or preservative packaging. Non-preservative packaging only protects the product from contamination and water loss, with the in-pack environment similar to the outside conditions. Preservative packaging, on the other hand, packages the product within an in-pack environment that differs from the external conditions to enhance the preservation of the food contents. Preservative packaging includes the use of gases, such as carbon dioxide or nitrogen, to replace the normal atmospheric air so that oxygen does not affect the food. Oxygen absorbing packets can also be placed in the packages to achieve the same effect.

To apply the packaging, these items undergo a batching operation. The batching machine forms tray-shaped or pouch-shaped packages from heat-scalable plastic films. Bulk packaging is typically applied to fruits and vegetables, as shown in the video above, due to the flexibility of their final package sizes. After freezing, food products are stored in bins of corrugated board or metal, with liners providing a moisture barrier and protection from contaminants such as dirt.

Quality Control

Many of the quality control measures implemented in the production of frozen foods are preventative measures. Strict sanitation of the equipment, along with proper preparation of the food before freezing ensures quality. Freezing food at the appropriate temperature is one way to ensure its quality and conformity. In addition, quick freezing prevents nutrition and moisture loss and also prevents ice crystallization, which could harm the protein and cell structure.

Beyond ensuring proper preparation steps, quality control of frozen foods also consists of discarding products, either before or after the food has undergone the freezing process, that do not conform to a certain standard, such as size, weight, and appearance. This is usually accomplished by having either a worker or automated system determine whether a product adheres to a standard and subsequently removing subpar items. In addition, samples are taken from each batch to undergo more rigorous laboratory testing to ensure quality.

Acknowledgments

- Wikimedia Commons, Beschneiden des abgeschwarteten Kotelettstrangs, Ralf Roletschek

- Wikimedia Commons, State Library and Archives of Florida

References

- Alessandro, Del Nobile Matteo, and Amalia Conte. Packaging for Food Preservation . Springer, 2013. Springer, link-springer-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/book/10.1007%2F978-1-4614-7684-9.

- Bohning, James J. Quality and Stability of Frozen Foods: Time-Temperature Tolerance Studies and Their Significance: a National Historic Chemical Landmark. American Chemical Society, Office of Communications, National Historic Chemical Landmarks Program, 2002.

- Campbell, Horace. Analytical Methods in the Food Industry; Collection of the Papers Presented at the Symposium on Analytical Methods in the Food Industry. American Chemical Society, 1950.

- Dauthy, M. E. (1995). Fruit and Vegetable Processing (United Nations). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Dunn, T. J. (2015). Food Packaging. In Kirk‐Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc (Ed.).

- Evans, Judith A. Frozen Food Science and Technology. Blackwell Publishing, 2008. Wiley Online Library, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781444302325.

- Hui, Y. H, et al. Handbook Of Frozen Foods. 1st ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2004. Print.

- Lopez, A. (1975). A Complete Course in Canning (10th ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Canning Trade.

- Marcotte, Michelle, and Hosahalli Ramaswamy. Food Processing: Principles and Applications.

- Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis, 2006. Print.

- United States, Environmental Protection Agency., Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards. (1995). Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors.

Developers

- Nuramani Saiyidah Binti Ramli

- Daniel Watza

- Austin Potter